Willie Nelson’s Soaring Benediction: “I’ll Fly Away” and the Promise of Freedom Beyond

When Willie Nelson turns his voice toward “I’ll Fly Away,” he breathes new life into one of the most beloved gospel hymns ever written. Though the song first appeared in the 1930s, penned by Albert E. Brumley while he worked in the cotton fields, Nelson’s tender interpretation—recorded and performed many decades later—has made it feel both eternal and personal. It is not a song that Nelson wrote, nor one that charted under his name as a single, yet it has become inextricably tied to his live performances, often surfacing in moments of reflection, remembrance, or quiet celebration. For many older listeners, hearing Nelson sing “I’ll Fly Away” is like hearing a prayer carried on the wind.

The song’s history is worth pausing over. Brumley composed it in 1929, drawing inspiration from an old prison tune—“If I had the wings of an angel, over these prison walls I would fly.” In his hands, that image of escape was transformed into something radiant: a vision of death not as an ending, but as a joyous departure into freedom. Published in 1932, “I’ll Fly Away” quickly became one of the most recorded gospel songs of all time, embraced by church congregations, bluegrass bands, and country singers alike. The Chuck Wagon Gang’s version in the late 1940s sold over a million copies, cementing its place as a hymn of the people.

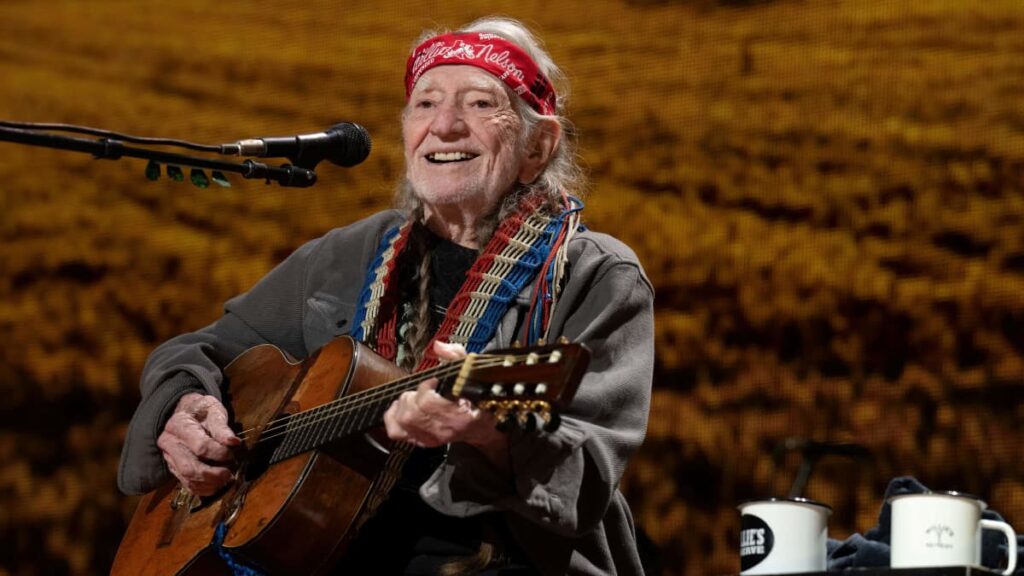

When Nelson took it on, he carried more than melody—he carried memory. His voice, weathered by time and softened by years of singing on the road, gives the hymn an intimacy that no studio polish could ever capture. Unlike some of his early chart successes such as “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” or “Always on My Mind,” this performance was never meant for radio dominance. It was meant for hearts. Nelson often performed it in concerts, particularly in later years, where the audience would fall silent, listening as though the song was speaking directly to each soul in the room.

The meaning of the hymn, of course, runs deeper than melody. It is about release, about the hope of leaving behind the troubles of this world for something brighter. For those who grew up in small churches, it recalls the sound of wooden pews, the faint rustle of hymnals, the harmony of voices rising together. For others, it may bring back the memory of funerals, where “I’ll Fly Away” offered a balm in the midst of grief, a reassurance that the story was not ending but changing.

Nelson’s version taps into both. He does not simply sing of flight—he inhabits it. His phrasing stretches like wings, his guitar strum steady as a heartbeat. For older listeners, it is impossible not to feel the pull of nostalgia: the Sunday mornings, the voices of grandparents now gone, the comfort of believing that beyond life’s trials, there is rest and reunion.

In the end, Nelson’s “I’ll Fly Away” is more than a cover; it is a benediction. It reminds us why songs endure—not because they climb charts, but because they speak to the human condition. This hymn, sung in Nelson’s voice, is both a farewell and a promise, a reminder that someday, when this weary life is over, we too will fly away.